2021 NHMA Legislative Bulletin 14

Primary tabs

LEGISLATIVE BULLETIN

Call Your Representatives NOW!

We hope everyone knows by now that the House has a three-day session scheduled for next week, April 7, 8, and 9, during which it will take final action on the approximately 350 House bills still in its possession (many of which are on the consent calendar). April 9 is its deadline to act on all House bills, so it must complete that action by the end of that day.

As we have explained several times, the agenda contains an unprecedented number of really bad bills that will restrict municipal authority, make local government more difficult, costly, and inefficient, impose new mandates, and increase taxpayer expense. We wrote about some of the worst bills in Bulletin #12 and Bulletin #13, and several more are discussed below (after the budget article).

Recognizing that there are too many to keep straight without a scorecard, we have compiled a list of the 20 bills we are most concerned about (in addition to the budget bills) that representatives can use for reference during the three-day session. Here is a link to the list. Please share it with your representatives—and talk to them about the most troubling bills, which we have highlighted.

House to Vote on Biennial State Budget

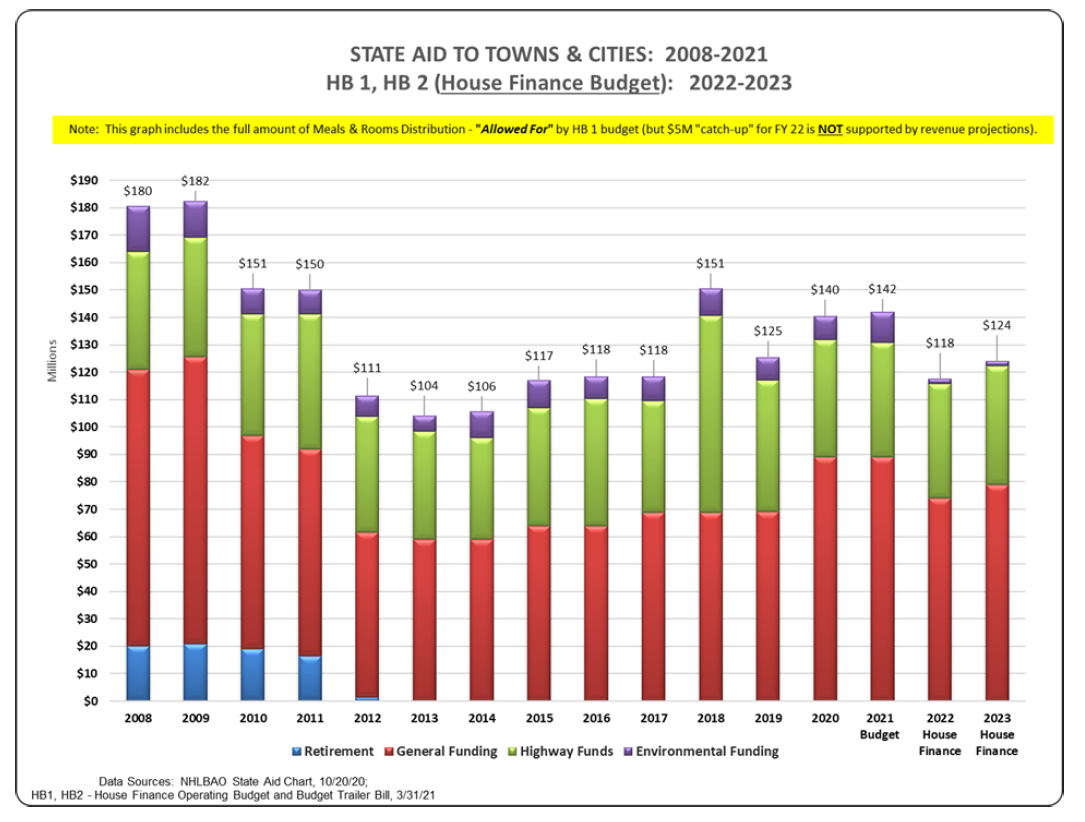

On Wednesday the House Finance Committee voted 12-9 along party lines to recommend Ought to Pass with Amendments on HB 1 and HB 2, the biennial state operating budget and associated trailer bill. Under the proposed budget, municipal aid and revenue sharing are $40.9 million less than the current biennium (see chart below). The House will vote on the two budget bills next Wednesday, April 7. The following is where things stand right now in terms of funding for cities and towns:

- Meals and Rooms Tax: $68.8 million (minimum) each year for meals and rooms tax distribution. For the first time since 2017, the statutory catch-up formula is not suspended in HB 2, thereby allowing (contingent on sufficient increases in year-over-year revenue) for up to $15 million in additional distributions ($5 million, FY 22; $10 million, FY 23), as appropriated in HB 1.

- Revenue Sharing: $0 each year. Suspended RSA 31-A, as has been the case since 2010.

- Highway Block Grant: $35.7 million and $37.2 million for fiscal years 2022 and 2023, respectively, for highway block grants (approximately equal to current biennium).

- Municipal Bridge Aid: $6.0 million each year for municipal bridge aid (a reduction of $1.6 million from current biennium). There are 113 enrolled municipal bridge projects through 2028—which include 66 of the current 243 “red list” bridges. Enrollment is currently frozen with a waiting list.

- State Aid Grants (SAG) $0 each year for existing state aid grant (SAG) payments previously awarded and approved by governor and executive council. HB 2 defunds 162 water pollution control projects in 56 political subdivisions—a reduction of $15.6 million from the governor’s budget. As we reported in Bulletin #12, HB 2 states that if unrestricted general fund revenues are above the budgeted plan on December 31, 2021, the commissioner of the Department of Environmental Services, “may,” with the approval of the legislative fiscal committee and the governor and executive council, request up to 50 percent of those funds to make grant payments. However, it does not provide any priority with regard to which projects might receive payment.

- State Aid Grants: $0 each year for new state aid grants for substantially completed, eligible water pollution control, water supply, and landfill closure projects. There are currently 11 water pollution control projects that were slated for funding in the current biennium but placed on hold due to the pandemic, and there are 110 additional projects identified by the Department of Environmental Services as eligible in the next biennium. HB 2 places a moratorium on all eligible state aid grant projects under RSAs 486, 486-A, and 149-M.

- Flood Control: $887,000 each year for reimbursements to municipalities involved in interstate flood control compacts.

We typically do not include in the Bulletin detailed information regarding education funding. However, we want to note that HB 2 (sections 354 and 355) includes changes to the education funding laws that would reduce the statewide education property tax (SWEPT) by $100 million, requiring that the state education tax rate be reduced to generate $263 million. HB 2 further requires that any municipality whose total education grant is decreased due to the SWEPT reduction would receive a supplemental education payment from the state’s education trust fund to satisfy the state’s obligation under RSA 198:41.

Assuming the House passes HB 1 and HB 2, the House version of the budget will go to the Senate, where deliberations will begin all over again with members of the Senate Finance Committee.

Remember that we are in the mid-stage of the state budget process, with many changes still likely to occur. For example, the budget is predicated on revenue estimates that have increased significantly in the past few months; and the month of April is historically one of the largest revenue months. Also, as vaccination rates continue to improve and the state moves toward re-opening, the Senate will have the advantage of working with updated, and possibly improved, revenue estimates. Perhaps of equal or greater impact, the U.S. Treasury is expected to release its guidance about the possible uses of American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) funds within the next 45 days. Based on current information, ARPA will likely help state budget writers plan for and direct these additional federal monies to fill current funding gaps of critical and essential state programs created by the pandemic. We will keep you posted in the Bulletin as this process proceeds.

Adoption of SB 2

In 2019 the legislature made a rare improvement to the law governing the so-called SB 2 form of town meeting. Under the new law, the question of adopting SB 2 is voted on at the town meeting’s business session, like almost every other town meeting question. Under the previous law, the question had been relegated to one sentence on the official ballot, leaving voters a few seconds in a voting booth to make up their minds on the most significant change a town meeting is ever likely to make.

The 2019 change has enabled voters to have a full, informed discussion at town meeting before voting. A perfect example occurred at the Bow town meeting this year, when more than a dozen residents debated and answered questions about the adoption of SB 2 for almost an hour. The arguments on both sides were well reasoned and informative and gave voters a better understanding of the issues. That is how a legislative body should work.

HB 374 would reverse the 2019 change (which passed by an almost 2-1 margin in the House and unanimously in the Senate) and reinstate the flawed process that encourages uninformed decision making. Despite overwhelming opposition and almost no support at the hearing (twenty-three people signed in opposition, one person in support), the Municipal and County Government Committee voted to recommend the bill for passage. Please urge your representatives to kill HB 374 next week.

Amending Petitioned Warrant Articles

Almost every year there is a bill to prohibit the voters in an SB 2 town from amending petitioned warrant articles. The House will be voting on another of those bills next week. With a proposed committee amendment, HB 67 would prohibit the voters at a town meeting deliberative session from amending a petitioned warrant article “to change its specific intent.”

The legislature has routinely killed these bills, and for good reason. In any legislative body, once a motion is made—or a bill is filed—it is subject to amendment by the body. For example, in the New Hampshire House of Representatives, once a bill is filed, any member may move to amend the bill; the only limitation is that the amendment must be germane to the subject matter. Similarly, at a town meeting, any voter may move to amend a warrant article, so long as the amendment does not change the subject matter.

A complaint often heard in support of bills like HB 67 is that only a small number of voters attend the deliberative session, and they should not be able to control what goes on the ballot. Yet HB 67 would leave an even smaller number of voters—the 25 who submitted the petitioned article—in control of what goes on the ballot. If the petitioners do not want to see their article amended, they need to muster the votes to prevent an amendment at the deliberative session. If they do not have the political support locally to achieve their goals, it is not the state legislature’s job to intervene. Further, there are many times when the petitioners themselves want to amend their article, just as a legislator who files a bill may want to amend it. HB 67 would not allow that.

The irony here is that the committee’s amendment to HB 67 would change the bill’s “specific intent”—yet it would prohibit voters at town meeting from doing exactly the same thing. Please urge your representatives to kill HB 67 next week.

Immigration Bill Will Subject Municipalities to Lawsuits

Another bill on next week’s House calendar, HB 266, is an unnecessary infringement on the authority of municipalities and creates the possibility of serious constitutional violations. The bill prohibits municipalities from adopting any policy that restricts or discourages “inquiring about the immigration status of any individual.” Police chiefs across the state and across the country have determined that municipalities are safer when residents are comfortable reporting crimes and otherwise cooperating with the police. Concern that the police will inquire about their immigration status severely erodes that comfort. A policy of not inquiring about immigration status is a useful means of improving police-community trust and enhancing public safety. Local authorities should be left alone to adopt the policies they believe are best suited to improving public safety in their cities and towns.

The bill also requires municipalities to “fully comply with, honor, and fulfill any instruction or request made in [a] detainer request and in any other legal document provided by a federal agency.” An Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detainer request is merely that—a request—and federal law does not require local authorities to hold anyone based on an ICE detainer request alone. Although there is disagreement on the subject, some courts have held that local and state law enforcement agencies violate the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition on unreasonable searches and seizures when they hold a person based on an immigration detainer request alone. By requiring local police departments to “fully comply with” ICE detainer requests, HB 266 creates a serious risk of liability on the part of municipalities for violating individuals’ constitutional rights. This risk will be even greater if the legislature enacts HB 111, discussed below.

The Municipal and County Government Committee voted HB 266 Ought to Pass, 10-9. Please urge your representatives to kill HB 266 next week.

HB 111 and Municipal Immunity: A Review

We understand that many people remain confused about what HB 111 does, and what its effects would be. That is not surprising. The bill deals with a complicated subject, and there are many competing claims about it. The following is a more comprehensive explanation of the existing law and the effects of HB 111 than we have written so far; but we hope it is fairly clear and simple.

Almost all of the discussion we have heard about the bill has centered on “qualified immunity” and why it should or should not be eliminated. As we have said repeatedly, the bill does much more than eliminate qualified immunity, so the focus on that doctrine is a distraction. However, understanding qualified immunity is necessary to understand the bill, so we will start with that.

Background—section 1983. The issue begins with a federal statute, 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which allows a person to sue a government official or employee when it is claimed that the official/employee committed an act that violated the person’s rights under the U.S. Constitution. A typical example is a claim that a police officer barged into a house and searched it without a warrant, thus violating the resident’s right to be free from “unreasonable searches and seizures” under the Fourth Amendment.

Qualified immunity. The federal courts have developed a doctrine called “qualified immunity,” which protects a government official or employee from liability under section 1983 if the official/employee’s conduct “does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.”

Many people have criticized qualified immunity because courts have applied it very generously—holding that under the “clearly established” standard, immunity applies if the specific conduct has not previously been determined to violate the constitution, regardless of how outrageous it may be. An often-cited example is Jessop v. City of Fresno, a 2019 case from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. In that case police officers obtained a warrant to search the plaintiffs’ premises and seize money and other property related to illegal gambling and money laundering. The plaintiffs claimed that the officers seized over $275,000 in cash and rare coins, but accounted for only $50,000. In other words, the police officers stole $225,000.

The court of appeals held that qualified immunity applied, because that court had never previously ruled that theft of property that is seized pursuant to a search warrant violates the Fourth Amendment. (The Fourth Amendment prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures—it says nothing about theft.) In other words, it was not “clearly established” that the conduct violated the plaintiffs’ constitutional rights. Thus, the police officers were immune from liability under section 1983.

The limits of qualified immunity. The Jessop decision sounds outrageous, and for the sake of argument, let’s concede that it is. But it does not mean that police officers face no consequences for heinous conduct. Qualified immunity protects only against liability under section 1983. It does not protect against criminal liability—and stealing $225,000 is certainly a crime. It also does not shield against common-law tort liability. The plaintiffs in the Jessop case presumably could file a common-law tort action against the police officers to recover the stolen money (and probably more).

Some people have cited high-profile cases of police misconduct as evidence of the need to eliminate qualified immunity. But again, qualified immunity does not shield anyone from criminal liability; a police officer who murders someone will not be protected by qualified immunity, and eliminating qualified immunity will not make that officer any more or less likely to be convicted (nor, for that reason, will it make a police officer any more or less likely to commit a crime). The failure to prosecute, or convict, an officer who commits a crime may indicate a problem with the criminal justice system, but qualified immunity has nothing to do with that.

Beyond qualified immunity—official immunity. Again, qualified immunity is only a part of the picture. Under New Hampshire law, a government actor is immune from common-law tort liability for discretionary actions within the scope of the person’s duties, so long as the actions were not taken in a “wanton or reckless manner,” and the person reasonably believed his or her conduct was lawful. This doctrine is called “official immunity.” Note that it is not nearly as protective as qualified immunity. A government actor who steals $225,000 would never be protected by official immunity, because that obviously constitutes acting in a “wanton or reckless manner,” and no one could reasonably believe it is lawful.

Beyond qualified immunity—RSA 31:104. The legislature has codified a variation of official immunity in RSA 31:104. That statute provides immunity from civil damages to certain municipal officials for actions taken in their official capacity “in good faith and within the scope of [their] authority.”

Qualified immunity and HB 111. Supporters of HB 111 assert that it will eliminate qualified immunity. It does that, in a roundabout way, but it does much more.

Because qualified immunity is a federal doctrine that applies in federal civil rights cases, the New Hampshire legislature cannot eliminate it. That power rests with Congress. Instead, HB 111 creates a separate cause of action, which would be filed in state court, for violations of the state constitution. Since the New Hampshire Constitution guarantees rights that are similar to and in some cases greater than those under the U.S. Constitution, HB 111 would give a plaintiff an alternative to filing a section 1983 action in federal court—the person could file an action in state court for a violation of the state constitution, and qualified immunity would not apply.

Eliminating official immunity and RSA 31:104. As stated above, HB 111 does more than eliminate state-level qualified immunity. It says that in an action against a “state agent” (which includes a municipal official or employee), it is not a “defense or immunity” that:

The rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the laws or constitution of New Hampshire or the United States were not clearly established at the time of their deprivation by the state agent, or that the state of the law was otherwise such that the state agent could not reasonably or otherwise have been expected to know whether the such [sic] agent’s conduct was lawful.

By disallowing the “clearly established” defense, this eliminates qualified immunity in claims for violations of state law or the state constitution—the stated goal of the bill’s supporters. But the bill then goes on to say that it is also not a “defense or immunity” that:

- The state agent acted in good faith; or

- The state agent believed, reasonably or otherwise, that his or her conduct was lawful.

This language repeals, respectively, RSA 31:104 (good faith) and official immunity (the employee reasonably believed the conduct was lawful). Thus, if a local official or employee does something that is subsequently determined to have violated a statute or a constitutional provision, it will be no defense that the person acted in good faith or reasonably believed his or her conduct was lawful.

Good cops and bad cops. A blunt way of thinking about this is that while qualified immunity—the federal doctrine—may protect good cops, it also has the potential to protect bad cops—the ones who steal $225,000 and are protected because it wasn’t “clearly established” that theft is unconstitutional. In contrast, official immunity—New Hampshire’s doctrine—protects only good cops—those whose actions are not wanton or reckless, and who reasonably believe their conduct is lawful. In the rush to take protection away from the bad cops by eliminating qualified immunity, HB 111 exposes the good cops, too. That is the problem.

Not just cops. To be clear, HB 111 does not affect only police officers—it applies to any “agent” of the state or a municipality. We have previously cited some examples of non-police situations that could lead to liability, but here are a few more:

- A fire chief conducts a fire code inspection under RSA 153 in a manner that she believes, in good faith, is authorized by the statute. The property owner sues for trespass and/or an unreasonable search, and the court disagrees with the fire chief’s interpretation; or the court determines that the statute itself is unconstitutional. Under HB 111, her “good faith” and “reasonable belief that her conduct was lawful” will not protect her from liability.

- At a state election, a town moderator, following the requirements of RSA 659:43 and 652:16-h, tells a voter that he must remove his hat because it bears the logo of a candidate. The voter sues the moderator for damages, claiming a violation of his First Amendment rights, and the court declares the statutes unconstitutional. Under HB 111, the moderator has no defense to the claim for damages.

- A welfare officer denies a resident’s request for assistance, applying a good-faith interpretation of the welfare statute, RSA 165. The applicant sues the welfare officer individually. The court acknowledges that the welfare officer’s interpretation is reasonable, but rules that it is incorrect. Under HB 111, the welfare officer has no defense.

Admittedly, in these cases the monetary damages are likely to be minimal, but under HB 111, the municipality will also have to pay the plaintiff’s attorney fees; and then there is the municipality’s own legal expense.

The risk to employees. Supporters of HB 111 continue to say that municipal employees do not need to worry, because the bill provides that they will not be financially liable. But they will still be sued in situations where they previously were immune—being sued is no fun, no matter how much money is involved—and the bill provides that they can be terminated if they are found to have violated someone’s rights.

The risk to municipalities. HB 111 makes a municipality liable for the actions of its employee. That is a huge departure from section 1983, under which a municipality is not liable for its employee’s actions unless it is shown that the municipality itself did something wrong—it adopted bad policies or it failed to train the employee properly. HB 111 essentially makes the municipality an insurer for the actions of a rogue employee.

Supporters of HB 111 have said the bill will create an incentive for municipalities to hire “better employees.” That is offensive—we are unaware of any municipalities that make it a policy to hire bad employees. There is already a shortage of applicants for jobs in police and fire departments, as well as for volunteers across the board—municipalities do not have the luxury of choosing from a large pool. A law that makes government employees liable for innocent errors in judgment will not make those jobs more desirable—so where will municipalities find “better employees”?

A problem in New Hampshire? At the committee hearing on HB 111 and during the discussions that have followed, not one New Hampshire case has been cited in which qualified immunity, or the other available immunities, led to a bad result. HB 111’s supporters have cited cases from around the country, suggesting that a change to New Hampshire law will solve the problem. We suggest that the out-of-state organizations pushing this bill should focus on the states where the problems exist.

Please urge your representatives to kill HB 111 next week.

SENATE CALENDAR

All hearings will be held remotely. See the Senate calendar for links to join each hearing. | |

|

|

TUESDAY, APRIL 6, 2021 | |

|

|

JUDICIARY | |

1:00 p.m. | HB 331-FN, relative to a forfeiture of personal property. |

Senate Floor Action

Thursday, April 1, 2021

HB 192, relative to pistols permitted for the taking of deer. Passed.

HB 258, permitting wage and hour records to be approved and retained electronically. Passed.

HB 342, relative to the taking of game by certain lever-action firearms and relative to the number of rounds permitted in a firearm used to take deer. Passed.

HB 354, relative to the local option for sports betting. Passed.

SB 67, relative to paid sick leave. Inexpedient to Legislate.

SB 96-FN-A, relative to implicit bias training for judges; establishing a body-worn and in-car camera fund and making an appropriation therefor; amending juvenile delinquency proceedings and transfers to superior court; and establishing committees to study the role and scope of authority of school resource officers and the collection of race and ethnicity data on state identification cards. Passed with Amendment.

SB 109, relative to municipal host customer generators serving political subdivisions. Passed with Amendment; Laid on Table. NHMA Policy.

SB 111, relative to claims for medical monitoring. Re-referred.

SB 132-FN, adopting omnibus legislation relative to COVID-19. Passed with Amendment; Laid on Table.

SB 142-FN, adopting omnibus legislation relative to certain study commissions. Passed with Amendment.

SB 150-FN, establishing a dental benefit under the state Medicaid program. Passed; Laid on Table.

SB 154, prohibiting the state from enforcing a Presidential Executive Order that restricts or regulates the right of the people to keep and bear arms. Passed with Amendment.

NHMA UPCOMING MEMBER EVENTS

Weekly | Friday Membership call (1:00 – 2:00) |

Apr. 13 | Webinar: ZBA Basics (12:00 – 2:00) |

Apr. 15 | Right-to-Know Law: Public Meetings & Governmental Records (1:30 – 3:30) |

Apr. 16 | Membership Call including 2021 Legislative Half-Time Report (1:00 – 2:00) |

Apr. 22 | Recycling 101: Municipal Solid Waste & Recycling in NH (9:00 – 12:00) |

Please visit www.nhmunicipal.org for the most up-to-date information regarding our upcoming virtual events. Click on the Events and Training tab to view the calendar. For more information, please call NHMA’s Workshop registration line: (603) 230-3350. | |