Understanding the Math, Dispelling the Myths

Primary tabs

The information contained in this article is not intended as legal advice and may no longer be accurate due to changes in the law. Consult NHMA's legal services or your municipal attorney.

This article, written by Barbara Reid, then NHMA Government Finance Advisor, first appeared in Town and City magazine in March 2013. It has been updated by Katherine Heck, NHMA Government Finance Advisor, where necessary.

The month of March, often described in terms of blustery weather patterns—“it comes in like a lion and goes out like a lamb”—is more aptly referred to by many as just plain old “mud season.” But the month of March also brings to mind other traditional images unique to northern New England: smoke rising from wooden sap houses, filling the air with the sweet scent of maple syrup; snow-laced crocuses opening their petals to the warming rays of an early spring sun; and, of course, the famous Norman Rockwell painting “Freedom of Speech,” which portrays the quintessential image of a traditional New England town meeting.

The convening of citizens at the annual meeting to conduct the town business at hand is a time-honored tradition in New Hampshire. One of the most important items on the agenda for that annual meeting is the adoption of the operating budget along with other appropriations necessary to pay for police and fire protection, maintains roads, and support many other municipal programs and services desired and expected by citizens.

Whether that meeting takes place in March, April or May, and whether that meeting is conducted in the form of a traditional town meeting (as depicted in the Norman Rockwell painting) or through the official ballot voting process known as SB 2, or whether that business is conducted by town or city councilors serving as the elected representatives of the citizens, the adoption of the town or city budget establishes the foundation upon which property tax bills will be based many months from now, when leaves are no longer budding, but falling.

Property taxes—the bill that so many love to hate! It’s the large bill that arrives generally twice each year in most communities, and the property tax rate, as well as the actual amount of tax on a particular property, is not known until long after the budget has been adopted. This often results in a significant disconnect between the spending priorities adopted in the spring and the tax bill that arrives in November or December.

The property tax system is the primary method of financing local governments in New Hampshire and, therefore, worthy of attention to dispel some of the myths and misconceptions associated with it. The property tax is a tax based on the value of real property. Cities, towns, village and special purpose districts along with school districts each raise money through the budget process and asses property tax. Local property tax also pays for a portion of the costs necessary to support county services, as well as the state education tax which every municipality is required to collect.

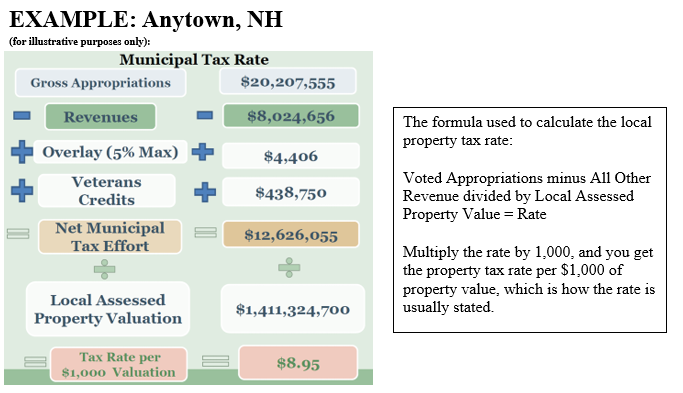

So how do budget appropriations, assessed value, exemptions, equalization and tax rate all work together to produce the bottom-line figure on the tax bill that every property owner must pay? We will start with the basic formula, and then discuss each component in more detail.

Setting the Tax Rate

Every fall, the Department of Revenue Administration (DRA) compiles all the information necessary to certify property tax rates for each municipality, reviewing all appropriations voted on in the spring and all revenues expected. The tax rate is determined by the amount of the tax levy (the amount of tax to be raised). There are several steps involved in determining the tax levy. The city/town develops and adopts a budget. Revenue from all sources other than the property tax (state aid, motor vehicle registration fees, permits and licenses, income from investments, etc.) is determined. These revenues are subtracted from the original budget and the remainder becomes the tax levy. When revenues are greater than estimated when the budget is adopted, the tax rate will decrease by the difference. When revenues do not meet the revenue estimates used when the budget is approved by the legislative body, the difference is made up by taxation.

By law, the property tax bill must show the assessed value of the property along with the tax rates for each component of the tax: municipal, local education, state education, county and village district (if any). Most municipalities receive the certified tax rates from DRA by mid-November, issuing bills that are then due in December—quite a while after the adoption of the budgets that established the basis for those property tax bills.

The amount of money which must be raised through taxes—appropriations minus all other revenue expected to be received—is the major factor which drives the property tax rate. The value of property is the basis on which the tax money to be raised is apportioned to each property owner.

Appropriations and the Budget Process

Every property owner is responsible for paying a portion of the taxes necessary to operate various units of government (municipal, school district, county and village district, if any). Each municipality, school district, village district and county must draft a budget, hold public hearings on the proposal and submit the budget to the legislative body for adoption.

Who are these legislative bodies that approve the necessary appropriations? For a town, the town meeting is the legislative body which appropriates money to operate the town. The school district meeting does the same for the schools, and the village district meeting does the same for districts. For a city, or a town with a town council form of government, the council (or board of aldermen) votes on appropriations. The county delegation, comprising all the state representatives from the county, appropriates the money necessary to fund county government. These appropriations determine the amount of revenue that must eventually be raised by property taxes in order to fund municipal government, and each municipality’s share of the school, state education and county budgets.

Valuing Property—The Appraisal Process

Property taxes are based upon the appraised value of property as of April 1 of each year. This means that the property tax bill, generally due in December, reflects the value of property on the previous April 1. By law, it is the responsibility of the governing body to annually determine the appraised value of the property within the municipality as of April 1. Most, if not all, municipalities rely on professionally trained assessors to fulfill this statutory responsibility.

Valuing property for property tax purposes is an ongoing process. By law (RSA 75:8-a), a municipality must perform a valuation every 5-years for all properties in the municipality’s boundaries. When, exactly, that occurs for your municipality depends on when it’s first valuation was reviewed by the Department of Revenue Administration (DRA). During a full revaluation, property is physically reviewed and then valued based upon the sale prices of other comparable properties or other approved appraisal methods. The goal of a revaluation is to appraise property at its “full and true” value, often referred to as “market” value.

A complete revaluation establishes base year property values, but is costly and time-consuming and, consequently, is not conducted every year. In the years following a revaluation, assessors perform updates in order to maintain proportionality between the properties in the municipality. They add to the tax rolls what are known as “pick-ups,” for example, new construction and other changes to properties. Depending on the amount of change reflected in recent sales prices and other market conditions, assessors may perform statistical updates, where values are adjusted either up or down based on market data, using a process beyond the scope of this article. Through revaluations and updates, assessors strive to ensure that property within the municipality is appraised proportionally as required by the New Hampshire Constitution, so that each property owner bears their proportionate share of the property tax based upon the value of their property—no more and no less.

Proportionality

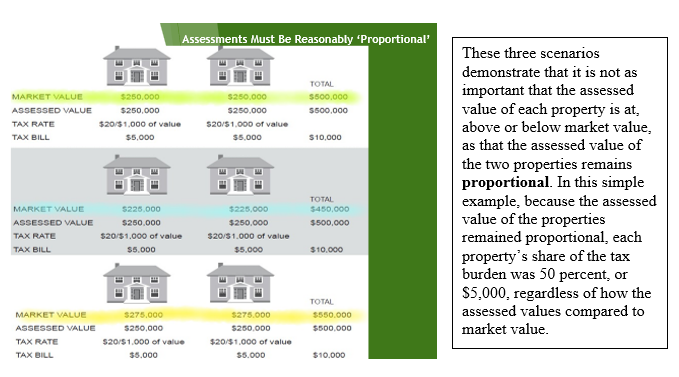

A frequent area of misunderstanding is the importance of assessing property values proportionally. It is not as important whether property is assessed at, above or below market value, as it is that values are proportional.

To explain the concept of proportionality, let’s look at a few simplified examples below. For the following scenarios, there are only two taxable properties in the town, the properties are very similar in all respects, and the legislative body has approved a $10,000 budget to fund town services, all of which will come from property taxation.

Scenario 1: Both properties have a market value of $250,000 as well as an assessed value of $250,000, for a total town-wide assessed value of $500,000. With taxes to be raised of $10,000, the tax rate would be $20 per $1,000 of valuation (10,000 ÷ 500,000 x 1,000). Since there are only two properties and they have the same assessed value, the tax burden would be shared equally: each property would owe $5,000 in property taxes.

Scenario 2: The town budget remains the same at $10,000, but the market has declined since last year so that the market value of each property is now $225,000. However, the assessed value on each property remains unchanged at $250,000. What is the impact of over-assessing these properties compared to market value? None—there is no tax impact, because the proportionality between the properties did not change; both properties declined in market value by the same amount. With taxes to be raised of $10,000 and a town-wide assessed value of $500,000, the tax rate would remain $20 per $1,000 of valuation and each property would again owe $5,000 in property taxes.

Scenario 3: The outcome is the same when the market value of the properties increases above the assessed value, in this case to $275,000.

What happens when one of these properties changes in value, but the other does not? Assume the market value of one of the properties dropped while the other property maintained its value, such as happened several years ago when the market for condominiums fell sharply. The condo, which once had a market value of $250,000, now has a market value of $200,000. If the assessed value of the condo remains at $250,000, both of these properties still would owe $5,000 in property taxes, even though the market value of the condo is $50,000 lower. This would leave the condo owner paying more than his or her fair share of the tax burden because the market value of the condo is less than the market value of the other property. Assessors can correct this lack of proportionality by using a statistical update. The assessor reduces the assessed value of the condo to reflect its drop in market value and to make it proportional to the other property. Now, both properties will be assessed at market value and both will pay only their proportionate share of the tax burden.

The Assessing Process

The assessing process includes the application of statutory exemptions and credits to the appraised values of properties. An exemption is a reduction in the appraised value of a particular property. A credit is a reduction from the tax bill on a particular property. The most common property tax exemptions are for property owned and used for governmental, religious, charitable, educational and other special purposes (for example, the solar exemption), as well as exemptions for elderly homeowners. The most common property tax credit is for veterans and their surviving spouses.

One of the misconceptions about property tax exemptions and credits is the effect that these have on the amount of taxes to be raised. Granting exemptions and credits for any purpose does not change the amount of property taxes that need to be raised—it merely shifts the responsibility for payment. While the exemption may benefit a particular property or one segment of the population, it will lower the tax base, resulting in a higher tax rate and increased taxes for those properties not eligible for the exemption. The same is true with property tax credits: if one property qualifies for a credit and, therefore, pays less in property taxes, then the amount of that credit must be made up by the taxes assessed on other properties.

Similarly, if a property tax exemption or credit is eliminated, it does not result in additional property tax revenue to the municipality. Rather, it increases the tax base, which lowers the tax rate and reduces the tax burden on other properties.

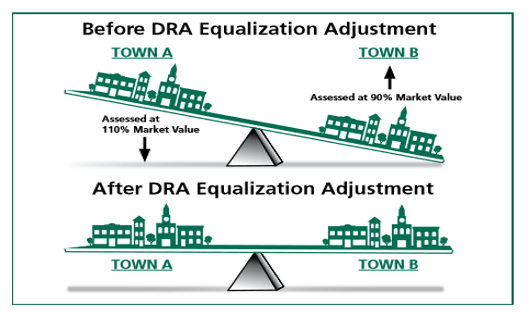

The Equalization Process

Some municipalities may be assessing property close to market value, while others may be assessing above or below market value, all of which is permissible. However, to ensure that public taxes shared by municipalities, such as the state education tax, cooperative school district taxes and county taxes, are reasonably apportioned among municipalities, the playing field must be leveled. This is accomplished by the annual equalization process conducted by the DRA through which each municipality’s assessed values are adjusted to reflect proportionality to other municipalities. This process involves a detailed study of property sales throughout the state, a comparison of those sales with the local property assessments, and an adjustment of the local assessed value up or down to achieve proportionality. The result is called the equalized assessed value.

Once the equalized value of property in each municipality has been determined, those shared taxes can be allocated based upon each municipality’s proportionate share. For example, if the equalized value of the property in a particular municipality represents 15 percent of the total equalized property value in the entire county, then that municipality would be apportioned 15 percent of the county taxes to be raised. Once the dollar amount of that municipality’s share of the county tax is known, the local assessed value is used to determine the tax rate and how much each individual property owner must pay.

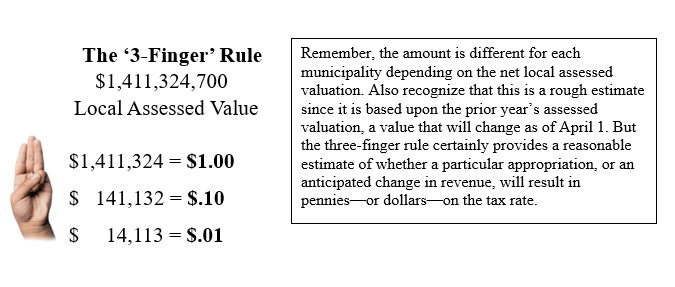

What Will That Add to the Tax Rate?

Before property tax bills are even mailed, the process begins again in many municipalities, as governing bodies and budget committees deliberate on the budget recommendations that will be presented at the next annual meeting. A question often asked at this time is “How much will this add to the tax rate?” To provide a ballpark estimate of how much a certain item will cost on the tax rate, DRA came up with the “three-finger rule.” Taking the prior year’s local assessed property value and covering the right three digits with three fingers provides an estimate of the amount of money that represents $1.00 on the tax rate. Covering the next digit would represent 10 cents on the tax rate, and covering one more digit would be a penny on the tax rate. This works for estimating both a change in appropriations as well as a change in revenues.

For example, in a municipality with $1,400,000,000 of assessed value, $1.4 million would be approximately $1.00 on the tax rate; $140,000 would be about $.10; and $14,000 would be about a penny. So, if a particular item, such as a new police cruiser, is estimated to cost $28,000, then, in this particular municipality, it would mean about $.02 on the tax rate.

Katherine Heck is the government finance advisor for the New Hampshire Municipal Association. Contact Katherine at 603-224-7447or kheck@nhmunicipal.org